“Yoga is contraction and expansion,” a yoga instructor once said as I settled into savasana. “All of life is.”

I think about this claim often.

Our hearts expand and contract. We inhale to expand and exhale to contract. Seasons follow a cycle of expansion and contraction—as does all of nature.

Perhaps, after this recent election you experienced the impulse to withdraw, cocoon. Or maybe instead you sprung like a coil, involving yourself in new forms of advocacy. Either way, you’re likely following your natural rhythm. Those cocooning will reemerge with energy for action. Those still fighting the fight will eventually need time to pull in, renew.

For many of us, December is a time of expansion—we’re more social, more mobile, more engaged with the outside world. January invites us to contract, to hibernate. Truth be told, even though I live in snowy, frigid Maine, January is my favorite month of the year. I love the quiet, the perceived pristineness of the new year, the permission to bury into work.

Our natural rhythms for expansion and contraction can be seen in our writing and revision as well. Many write first drafts in an expansive state where more beats less every time. Pages grow, discoveries are made. Everything is allowed in these unwieldy drafts. “Come in! Come in!” the writer says. “Stay for now, I may need you.” These initial drafts are an abundance of riches and will eventually need to be whittled—or even hacked—down.

Others, like myself, write in a more contracted state. (For years I wrote curled up in the corner of a chair.) I don’t outline, but I do write very slowly—slowly enough to condense sentences in an effort to distill their richest meaning. My first drafts are sparse landscapes, winter landscapes. Revision requires letting the buds open up, the story to swell. My initial drafts require rain, lots of rain. And air.

No matter which way you begin a story, it’s likely you beat yourself up a little bit over your method. How many times have I admonished myself for not writing more loosely? For retaining control rather than letting it rip? I suppose as many times as the expansive writer admonishes themselves for not considering an outline, for not writing with more awareness of structure.

Do I change? No. I bet you don’t either. Perhaps our writing styles reflect our way of operating in the world. But I suspect we choose to overswing in one direction or the other when beginning a new project because young work requires a great deal of faith, and leaning into our preferred method gives us more confidence. Expansive authors speak of needing frequent surprises to give them a sense of trust. Those of us who write in a more contracted way gain confidence when we drill down into new truths. (Not unlike poets I suspect who prefer a short, concise form.)

Neither the expanded method nor the contracted method of writing a first draft trumps the other. What matters is that we put the ideas down. The hard work comes in the revision, of course, because now we have to use the mode we’re less comfortable with. Those who added, added, added must reexamine and let go of sentences that once felt brilliant. Those who composed tight little knots must find ways of untangling them to allow for more messiness. More life.

Fortunately, whether you are a person who overwrites or underwrites, there are helpful ways of examining your work in revision. Here are two methods I recommend.

For Those Who Overwrite

If you’ve known me for a minute, you know that I’m a big fan of William Sloane’s THE CRAFT OF WRITING and, in particular, his views on density. Here are my favorite quotes by Sloane:

Density is one of the most difficult aspects of fiction to discuss because it is not a separate element like plot or even characterization. Rather it is a part of everything else. Real density is achieved when the optimum number of things is going on at once, some of them overtly, others by implication.

Writing is not a matter of a single, simple progression, with each sentence making only one point. Every paragraph, every sentence is related to the entire rest of the book, and if it is not so related it is superfluous. By ‘entire rest of the book’ I mean what is to come as well as what has gone before.

The enemy of fictional density is the one-thing-at-a-time scene, that simply shows you, the reader, one of the facets of the story, whether it be something about the characters or about the action or the setting, or whatever.

Density is the opposite of thinness. In its nature it is not divisible. It is not made by lamination but by fusion.

It is always there, any place at all in the book. An editor can open a manuscript to any page and tell its presence or absence… This omnipresent quality of successful fiction is extremely easy to recognize once you have learned to look for it. In order to see it in all its complexity, you might reread some books that you’ve read recently. Reread while the whole book is sharply present in your mind. See how you become aware of the fusion and the density…

At first, it may look as if density requires expansion—the addition of layers. And for some writers, it may. However, for those who overwrite, a close examination of density often brings about a good deal of condensing. Unnecessary repetition goes. Sensory details (as lovely as they are) that do not provide deeper meaning (as Sloane would say that are unrelated to the entire rest of the book) are deleted. Hollow dialogue, characters who play the same roles, background information that has already been introduced or is unnecessary seldom make the density cut.

Remind yourself that contraction isn’t loss, it’s culling for a more rewarding reading experience.

For Those Who Underwrite

During our recent R(ev)ise and Shine! community gathering, I brought up a conversation between Mitzi Rapkin and Elizabeth Rosner that was recorded on Mitzi’s First Draft podcast.

During the episode (and in her new book THIRD EAR: REFLECTIONS ON THE ART AND SCIENCE OF LISTENING) Rosner discusses a study done by Mortin Norgaard and Mukesh Dhamala in which these scientists examined the brains of musicians while improvising and discovered that when we are completely immersed in an activity (flow state) a smaller part of our brains are working while other parts of the brain go quiet. Rosner suggests in order to write more freely—with less intention and more improvisation—we practice shutting down the editorial mind for brief spurts of time. (Both the scientists and Rosner believe we can train our brains to work in this flow state at will and for longer periods.)

So begin by setting a timer for ten minutes. Tell yourself that you are going to write fast, without judgment, accepting whatever bubbles up. (Think of the “Yes And” rule in theatrical improv where you accept whatever direction your partner(s) take.) If your thoughts cease during this time, do not lift the pen. Create spirals on the page until more ideas come. (Or type I will not stop, I will not stop.)

See if you can’t expand the time from ten minutes to twenty. Write with abandon. What unexpected gems arrive?

To sum it up . . .

Remembering that expansion and contraction are natural processes, and that one follows the other helps. We can lean into our current state knowing it’s temporary, knowing that having had a good spell of one we’ll yearn for the other.

Also at our community gathering, writer Melissa Killian quoted V. E. Schwab, CITY OF GHOSTS: “There’s a difference between wanting to stay and being too afraid to let go.”

Perhaps for the time being you are exactly where you need to be. But when the time comes to switch, whether you’re in a state of expansion and need to contract, or you’re in a state of contraction and need to expand, the action (in writing and life) is the same.

Go ahead.

Let go.

Happy Holidays!

Jen

Announcements:

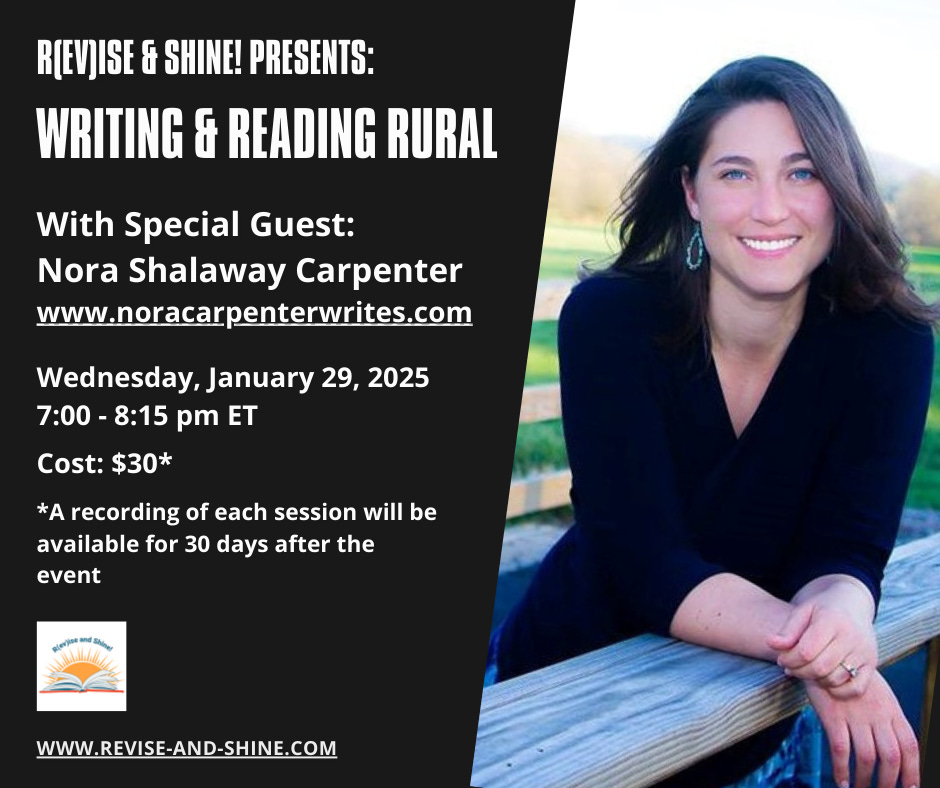

Writing - and Reading - Rural with Nora Shalaway Carpenter

(Or, With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility)

Whether you consider yourself rural or not, chances are you’ll write at least one rural character in your career. While an abundance of media continues to perpetuate rural stereotypes, writers are increasingly aware of the importance of portraying rural characters as nuanced and complex as their real-life counterparts. The how of this, though, continues to trip up even the most well intentioned of writers. This Zoomie offers a practical guide to help you avoid inserting common unconscious biases into your story, whether you are rural or not. To put our topic into context, we’ll begin with a brief overview of what literacy scholar Sara Webb-Sunderhaus calls “tellable” vs “untellable” narratives, focusing on how rural people often code switch depending on their audience and how you can use this knowledge to create fully fleshed out characters. Prompts will help participants construct and/or identify not only their characters’ belief systems, vocabularies, and appearances, but also what those rural characters feel about where they’re from and the people around them. Importantly, we’ll discuss different ways to show (rather than tell) those characteristics. We’ll also address “the dialect dilemma.” Additionally, participants will receive a handout on diverse rural resources and suggested mentor texts. The Zoomie will end with a Q&A.

When: Wednesday, January 29, 2025 from 7:00 to 8:15 pm ET

Where: Online

Cost: $30*

*For those who can’t attend live, a recording of each session will be made available for 30 days after the event for all ticket holders.

Click the image below to find out more and sign up:

Nora Shalaway Carpenter is an award-winning author, writing educator, and audiobook narrator. Her newest novel FAULT LINES won the 2024 Green Earth Book Award for YA, the 2024 Nautilus Book Award Gold Medal for YA, and is a Whippoorwill Book Award long list selection, among other honors. Her books have made numerous prestigious lists, including "Best of the Year" by NPR, Kirkus Reviews, Bank Street Books, the Texas Library Association TAYSHAS state reading list, and the Library of Congress's Discover Great Places Through Reading list. Her works have won accolades including the Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection, the Whippoorwill Award for authentic rural fiction, and the Nautilus Award championing "better books for a better world." She holds an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts and serves as faculty for the Highlights Foundation's Whole Novel Workshop. A neurodivergent author with an invisible disability, she champions busting stereotypes of all kinds. Visit her at noracarpenterwrites.com.

The Writers’ Book Club: Reading the Caldecotts

The Writers' Book Club hosted by R(ev)ise and Shine! focuses on specific questions of craft in order to become better at reading like writers.

For our next meeting we'll be discussing:

The winners of the 2025 Caldecott Medal and Honors!

This is an unusual Book Club for us, as we won't know which books we're actually reading until they are announced during the 2025 ALA Youth Media Awards presentation on Monday, January 27, 2025!

We’ll be sending an update via the newsletter once the winners have been announced.

$1.00 minimum dues to attend ($5.00 suggested)

Click the image below to find out more and sign up:

Love this and you, JJ! Thank you!!!