A few days ago, Rob e-mailed Jen, Lesa and me to remind us that we had a newsletter deadline coming up. The task seemed daunting to all of us, given what had just happened. I suggested we write a collective message to you all, something to let you know we’re thinking of you, that our community is here, etc. This felt urgent and necessary. I volunteered to write the first draft, and then we could edit it together. The morning I wrote this, in my usual 4 a.m. way, I was wide awake, trying to write a draft in my head. Every time I tried, the words came out with “I” instead of “we.” It didn’t feel right, trying to put all four of our thoughts together in this moment. We are each hurting from this news in different ways and for different reasons. The implications for me are different than they are for Rob, Jen and Lesa. We come from different backgrounds and experiences. We live in different states. We are a diverse little group, and that means a lot right now. I can’t speak for them. But I can feel for them. And I can feel for all of you, as well. Deeply. And I do.

The last time Trump won the election, I wrote an essay about it. I re-read it this morning and thought… Yup, this is it all over again. This is it exactly. I won’t share the whole thing. I admit it’s far too personal and I feel far too vulnerable at the moment to do that. But I will share a bit of it. Mainly, because I do see the hope there, in my bruised, defiant tone. And I hope you’ll feel it, too.

Note: This was a love letter of sorts to the students and faculty in the MFA program where I teach. “We” refers to all of us, gathering back at our winter residency. The lecture I refer to in the opening paragraph was given by the director of the program shortly after the election, and my response is one year later.

On Writing After The Election: Part Two

One year ago, we gathered in this room for a lecture called "Writing After the Election." I sat in the front row, ready (desperate) for wisdom. How do we write after the election? How do we keep our rage at bay, as we try to meet deadlines, and keep on writing what we always have, when the pussy-grabbing video keeps playing in the background, or at least in our minds. How do we stay sane when yet another man—or maybe worse, a woman—dismisses it all as "locker room talk?"

When the slide of the lynx skull appeared on the screen, bloody and grotesque and not recognizable as a lynx but certainly something that was once a living creature, I winced and looked away, not only because it was such a hard thing to see, but because it was a hard thing to witness and, somehow, I felt it was wrong to look.

In the days leading up to the workshop, we'd heard rumors that someone had hit a lynx on their way to residency, put the body in the trunk of their car, and smuggled it into their hotel room. There, the stories went, the lynx had been skinned in the bathtub. I had convinced myself these rumors were too outrageous to be true.

The lynx's eyes were gone.

That's how I remember it, anyway. Or maybe I just couldn't look at her eyes. I say her because that would make the most sense. That the now-legendary lynx projected on a large screen in the Dodge parlor, helpless—no, dead and exposed—would be female. Don't tell me if I'm wrong.

What Ben said about the lynx was described beautifully by Leslie Jamison in her introduction to Best American Essays 2017: "My friend decided to use this lynx skull as a prop in "Writing After the Election." He would set the skull in the middle of his desk—at the front of the room—and begin to speak about the role of creative writing in our time. At a certain point, he would say that writing without letting politics into your work was like trying to describe this room without ever mentioning there was a bloody lynx skull in the middle of it."

For someone who sat here that day, with the bloody, vacant-eyed skull exposed on the screen for what felt like an eternity, the lynx felt even more powerful than that. The question for me became not, "How do we write after the election?" but, "How do we function as women after the election?" The bloody lynx skull in the middle of the room, who had been skinned and exposed and exploited, represented what was happening to every woman who'd been grabbed and was now feeling grabbed all over again every time that damn video showed up in our news feeds followed by the "locker room talk" dismissal.

Writing after the election is like writing after your skin has been ripped off. In Martin Luther King Jr.'s words, there is suddenly "a fierce urgency of now," to do something about it. Hash tags called on women to share their stories in an effort to link us, to empower us, and to make us feel less alone. To speak. To write. To show the world what's under that bruised skin of ours.

There's a workshop Amy Irvine gives called "The Epiphanic Moment" and in it she has students place themselves in a scene they've written using chairs and other students as props to set an intentionally crude and bare stage. The writer of the scene then walks us through her imagination or memory, giving detailed descriptions—both physical and emotional—to fill in the holes on the written page. It's a brilliant method, really, because it shows the writer and everyone participating that what's missing on the stage we've tried unsuccessfully to set, is also missing in the writing itself. And what's almost always missing, I've observed, is the truth.

Many years ago, my writer friend Jennifer Jacobson said that when she feels close to finishing a book, she asks herself, "Is it true yet?" Has she revealed the big reason for writing the story in the first place? Has she figured out what that is, and exposed it? Usually, attached to the truth is shame and fear, and it is HARD to be true in our work when those pieces play a role.

Even victims have guilt.

JJ showed me what was missing in my own as-yet un-published work. I needed to make my characters more honestly flawed—more true—in order to make them real. And I've learned over the years that the stories of my life are mostly the same. I am a victim, but the truth is I am also guilty.

The settings in my memories resemble Amy's. There might be a chair, and a girl, and a feeling of shame and fear. If Amy stepped on the scene, the transcript of my life in her hand, she would stand beside this girl and start asking questions. Who are you with? Is it hot or cold? What do you hear in the background? What are you wearing? Who is looking over your shoulder?

Now, as I try to remember the details and write this essay, I see the lynx skull. I feel her watching me through vacant, hollow eye sockets. I want to protect her and, gruesomely, I want to be her. This lynx. This cat. This pussy. I want to occupy her body, bring her back to life, and grab back.

As Oprah said at the Golden Globes, "Speaking your truth is the most powerful tool we all have." So here I go.

What follows in that essay is my truth, and my journey to reckon with it. Throughout, the lynx follows me. She is there, giving me courage. Power. She will always be “in the room,” just like she was all those years ago. I cannot write without acknowledging her presence, just like Ben alluded to.

A few months after I shared this essay, my husband encouraged me to do something very much out of my comfort zone. At a Fourth of July parade a woman had handed me a flyer for an information session about roller derby. “She picked you,” my husband said. He was convinced it was meant to be. I was scared. I didn’t think I was strong enough. I was shy. I hadn’t put skates on since the 6th grade, and now I was 48 years old. It was a silly dare, but, at the same time, something about it felt exciting. I went. And it changed my life. When I passed through all the skills levels needed to qualify to play, I finally chose my derby name.

Now, when I put on my helmet, I really do become the lynx. I feel her inside me, giving me strength, just like she did when I told my story—the truth—all those years ago.

Here is how I ended my essay:

How do we write after the election? How do women write after the election—our pelts peeled off, leaving us vulnerable but exposed as human—not simply female, but wholly? These two things are entwined for me. They claw their way through the dense fog on a freezing cold night, wishing I could simply cross the road safely and continue into the darkness.

But instead, I must try over and over—no—we must try over and over—to stop and stand before the glaring headlights and desperately answer the question, in its fierce urgency of now: "Is it true yet?"

We are all experiencing the results of the election differently. That is certainly true. But what is also true is that we are a community that can experience these feelings together. We can be silent, and step into the darkness, or we can stand before the headlights once again and face the truth head on. We can speak it, in our own unique ways. Even though that means something different for each of us, we don’t have to do it alone. We can link arms. We can hold our ground. We can lift each other up. We can yell. We can cry. We can mourn. We can fight. We can do all of these things, united in our need to stand our ground. To keep speaking. To keep writing. To keep searching for our own truths and express them in our own special ways.

Somewhere out there, a reader is waiting to hear your story. To be moved and changed by it. Maybe even be saved by it. And that is worth all the effort. It has to be. Whether as Lynx, or Jo, or both, I am standing right beside you, I am in the room, ready to listen. We all are.

In community,

Jo

Announcements:

R(ev)ise & Shine! Presents: A FREE Year-End Community Zoomie!

As 2024 draws to a close, Lesa, Rob, Jo, and Jennifer invite you to join us for this fun, relaxed, and free community gathering. We'll ask you to talk about your writing successes and struggles this year and share your goals for the next.

To get the conversation going, we request that you bring 1-3 sentences from a published work (not your own) that you really admire—and then say a word or two about why you picked this selection.

We hope you'll join us to celebrate, in community, the good work we've all done in 2024!

When: Wednesday, December 4, 2024 from 7:00 to 8:00 pm ET

Where: Online

Cost: FREE

Click the image below to find out more and sign up:

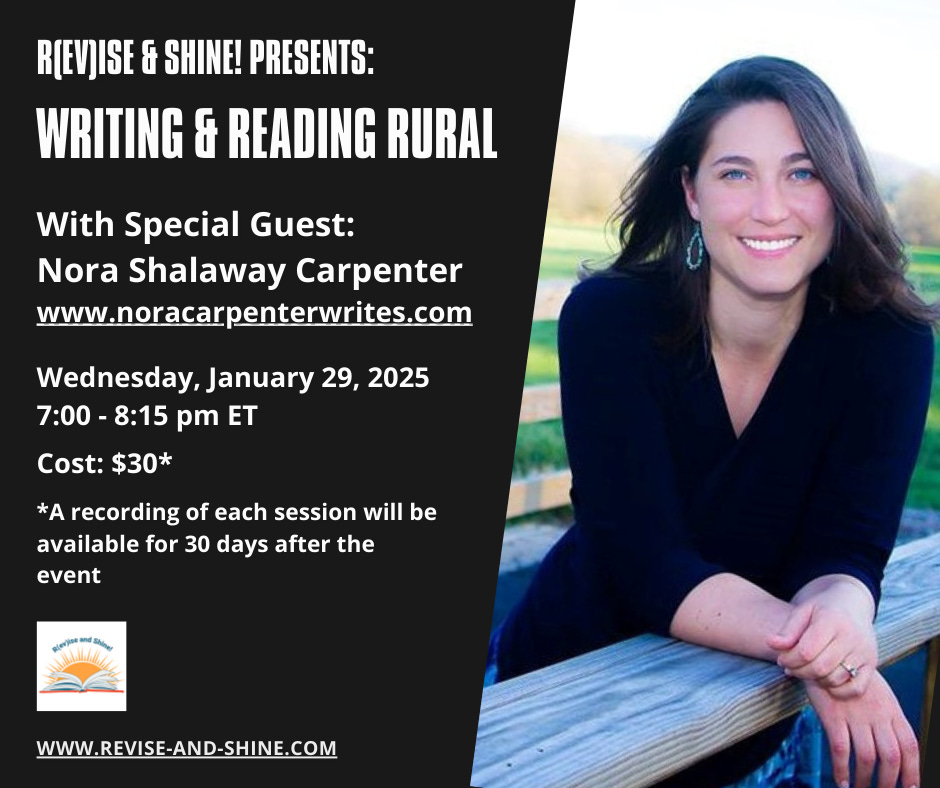

Writing - and Reading - Rural with Nora Shalaway Carpenter

(Or, With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility)

Whether you consider yourself rural or not, chances are you’ll write at least one rural character in your career. While an abundance of media continues to perpetuate rural stereotypes, writers are increasingly aware of the importance of portraying rural characters as nuanced and complex as their real-life counterparts. The how of this, though, continues to trip up even the most well intentioned of writers. This Zoomie offers a practical guide to help you avoid inserting common unconscious biases into your story, whether you are rural or not. To put our topic into context, we’ll begin with a brief overview of what literacy scholar Sara Webb-Sunderhaus calls “tellable” vs “untellable” narratives, focusing on how rural people often code switch depending on their audience and how you can use this knowledge to create fully fleshed out characters. Prompts will help participants construct and/or identify not only their characters’ belief systems, vocabularies, and appearances, but also what those rural characters feel about where they’re from and the people around them. Importantly, we’ll discuss different ways to show (rather than tell) those characteristics. We’ll also address “the dialect dilemma.” Additionally, participants will receive a handout on diverse rural resources and suggested mentor texts. The Zoomie will end with a Q&A.

When: Wednesday, January 29, 2025 from 7:00 to 8:15 pm ET

Where: Online

Cost: $30*

*For those who can’t attend live, a recording of each session will be made available for 30 days after the event for all ticket holders.

Click the image below to find out more and sign up:

Nora Shalaway Carpenter is an award-winning author, writing educator, and audiobook narrator. Her newest novel FAULT LINES won the 2024 Green Earth Book Award for YA, the 2024 Nautilus Book Award Gold Medal for YA, and is a Whippoorwill Book Award long list selection, among other honors. Her books have made numerous prestigious lists, including "Best of the Year" by NPR, Kirkus Reviews, Bank Street Books, the Texas Library Association TAYSHAS state reading list, and the Library of Congress's Discover Great Places Through Reading list. Her works have won accolades including the Junior Library Guild Gold Standard Selection, the Whippoorwill Award for authentic rural fiction, and the Nautilus Award championing "better books for a better world." She holds an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts and serves as faculty for the Highlights Foundation's Whole Novel Workshop. A neurodivergent author with an invisible disability, she champions busting stereotypes of all kinds. Visit her at noracarpenterwrites.com.